Research

Bubble dynamics in Gels and Yield-Stress Fluids

I have recently been studying how small bubbles behave in complex fluids. Our aim was to understand if the complex fluid modified the behavior of the bubbles in such materials, for instance if they prevent the bubble from dissolving, or if they prevent them from rising or if it affects their shape while they rise.

Bubbles have an additional trick up their sleeve, though. They can be excited by ultrasound. They resonate following a well-known resonance curve in Newtonian fluids, with a resonance frequency inversely proportional to its size. We have investigated whether using a yield-stress material changes that resonance.

For a larger excitation amplitude, we can even wonder whether oscillations may have an impact on the structure of the nearby gel. It is not clear yet whether oscillations are directly responsible for these rearrangements, or if they are a product of our confined Hele-Shaw geometry. Additional experiments would be welcome to confirm if this effect can be achieved far from any boundary in a gel. This represents quite a challenge for confocal imaging.

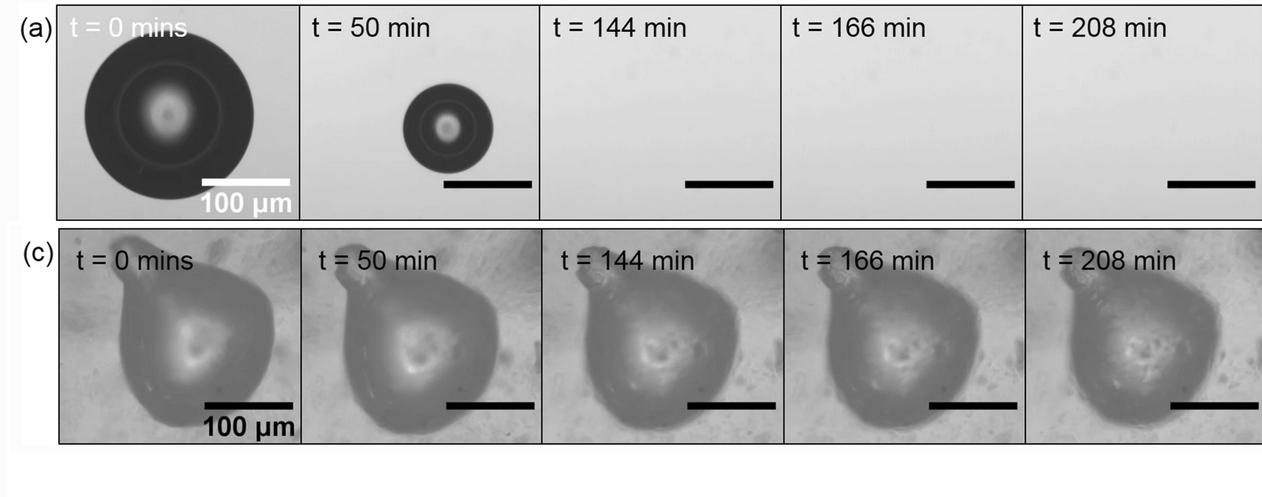

Halting bubble dissolution : Top : simple liquid. Bottom : paraffin wax oleofoam. The presence of both interfacial and bulk effects block the dissolution in the oleofoam. From S. Saha et al., Rheol. Acta. 59, 255–266 (2020)

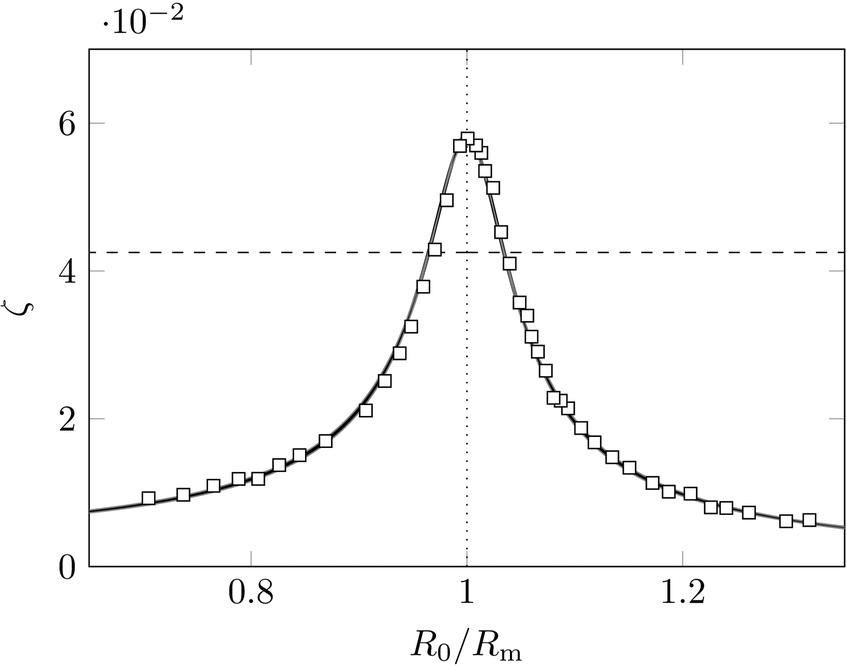

No impact of the Carbopol rheology on bubble resonance

Yield-stress fluids are thought to be solids under small deformation and significantly more viscous than, e.g. water under large deformation. In our case, though, our bubble trapped in Carbopol - a polymer microgel swollen with water, and a canonical yield-stress fluid - resonates as if it were simply immersed in water.

From Saint-Michel & Garbin, Soft. Matt. 16, 10405-10418 (2020)

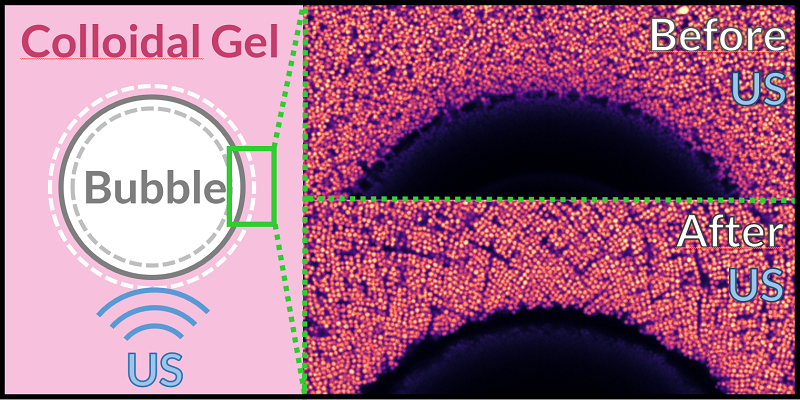

Local rearrangements near an oscillating bubble

Here, a pancake bubble (in black) has been injected in a thin slab of an attractive colloidal gel. The structure of the gel around the bubble changes once we apply an ultrasound excitation. This does not happen if no bubble is present.

From Saint-Michel et al., Soft. Matt. 18, 2092-2103 (2022)

Resuspension of concentrated, non-Brownian suspensions

I have studied concentrated suspensions, with the help of my colleagues from Lyon and Bordeaux, Hugues Bodiguel (now in Grenoble), Guillaume Ovarlez and Steven Meeker (from Solvay). I had initially been hired to examine how well particles could be resuspended in complex fluids compared to the Newtonian case. The aim of these expermients was to examine whether we could reduce the environmental impact of hydraulic fracturing by using less sand or proppants, since those usually sediment quite fast when they are flowed into the rock. Questionable impact for the environment, but better than doing nothing, I guess.

Resuspension is a rather simple experiment : you let particles settle in a fluid, before applying a shear. Even at vanishingly low Reynolds numbers, your particles in the sediment will bump into each other while passing by one another, and they need space to do that. The particle sediment will then expand a bit to allow these movements.

Resuspension experiments in these complex fluids were quite difficult, and even repeating the classical experiments from the literature with Newtonian solvents led to contrasted results between Lyon and Bordeaux. We then decided to join our forces and took advantage of having X-ray imaging equipment to examine the resuspension process in a Newtonian fluid. Surprisingly, it was shown to be shear-thinning even though there is no real reason for such a behaviour.

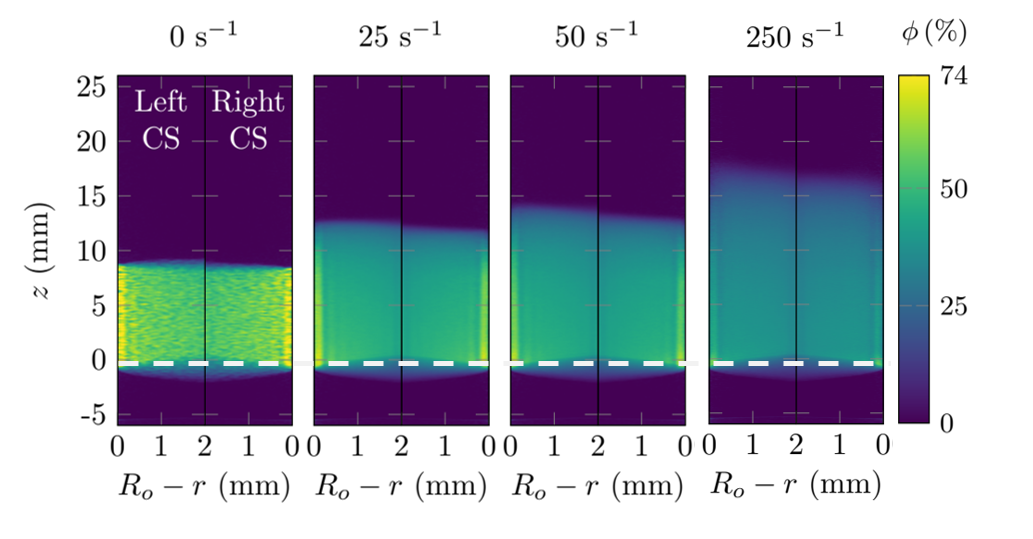

Concentration maps at rest and under shear

Profiles obtained through X-ray absorption in a Couette geometry. We show here two cross-sections of interest of our geometry being to the left and the right of the rotating spindle.

X-ray maps of the suspension absorption converted to concentration maps at different strain rates in a concentric cylinder (Couette) geometry. The left and right lateral cross-sections (CS) are shown. The asymmetry of the experiment is visible. From Saint-Michel et al., Phys. Fluids 31, 103301 (2019)

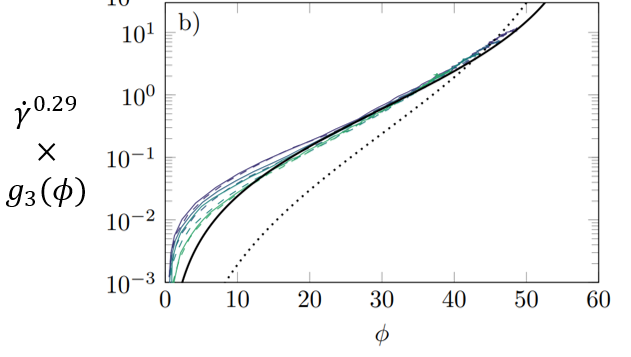

(Rescaled) Normal viscosity under shear

The quantity g(phi) called the normal viscosity should only be a function of phi, and experimental curves should collapse without applying the rescaling with the strain rate. We showed however that the collapse was better with this additional rescaling.

A purely Newtonian suspension should have a universal viscosity (g_3) with the volume fraction (phi). The additional rescaling with a positive exponent (0.29) indicates shear-thinning. From Saint-Michel et al., Phys. Fluids 31, 103301 (2019).

Past : Shear-Thickening Fluids

Shear-thickening fluids are very puzzling fluids. Simple liquids, usually composed of simple molecules or atoms (glycerin, water, honey, ethanol or mercury) are Newtonian (yes, that Newton), which means that to strain them at a certain rate, you have to apply a stress proportional to it. The proportionality ratio between these two quantities is the viscosity of the fluid.

Wait, what ? Newtonian ?

Shearing a slab of heterogeneous material.

Shearing a fluid (here, a blue liquid and gray circular particles) consists of sliding the top and the bottom boundaries in opposite directions (blue arrows) parallel to the boundaries. Sliding is done at constant speed. We can define a rate of deformation by dividing that speed by the thickness of our slab. We can also define the shear stress as the sliding force we need to apply divided by the area of the block of fluid in the horizontal direction. For a Newtonian fluid, the stress and the rate are proportional to each other.

Complex fluids

More complex fluids, made either of very long molecules (polymers) or made of a dispersed medium in another (foams, emulsions, …) are non-Newtonian, and flow more and more easily as you apply a strong stress onto them. Their viscosity decrease with an applied stress, and is quite well understood. The reverse behaviour, shear-thickening, also exists, but we don’t really understand it so well. A fairly easy way to create a shear-thickening fluid is to mix 2/3 of cornstarch and 1/3 water, as suggested by many many recipes existing on the internet. Such a behaviour is really really not intuitive from our day-to-day life experience: flowing these materials gently is easy, but trying to stir them too hard or fast and they suddenly resist a lot.

Quite a lot of progress has been done recently on the topic, and even if some authors still debate it, a consensus is emerging to describe shear thickening. To make it appear, you need hard grains in a fluid, and they need to weakly repel each other. If you shear them too hard, you suddenly beat that weak repulsion. In turn, the grains come into contact with each other, and they can no longer slide off each other. Having fewer degrees of freedom to move past each other, they suddenly resist deformation a lot more than they used to.

At least, this plausible scenario is what happens when you mix all these physical ingredients to make a realistic numerical simulation of a shear-thickening fluid. Rather smart experiments have confirmed that particles could indeed coming into contact with one another by studying what happens to the shear stress when you suddenly reverse the direction of shear. Additional experiments have neatly shown that by controlling the amount of salt in their suspension, i.e. by controlling the repulsion between particles, they could indeed go from frictional to ‘frictionless’ suspensions.

Smart people studying cornstarch

Video to the right : Prof. H. Jaeger (U. Chicago) and Dr. S. Waitukaitis (now at U. Wien) mix some cornstarch, then gently stir it before trying to punch it. Punching it seems to hurt.

Open questions and trying to address them

How do contacts they form and break ? Is it a local process, or a completely collective one ? Is the number of contacts steady, or fluctuating a lot ? What forces do they actually withstand ? These are very difficult questions to answer, and we need all the information we can to answer it. We have modestly attempted at contributing to the subject. To do so, we have used ultrasound echography to probe at the mesoscopic scale what happens in a shear-thickening fluid sheared under a constant stress. This is the setup you see below. After many months seeing strange artifacts in what were otherwise very nice, featureless velocity maps, we eventually realised that these artifacts were actually what we wanted to isolate all along !

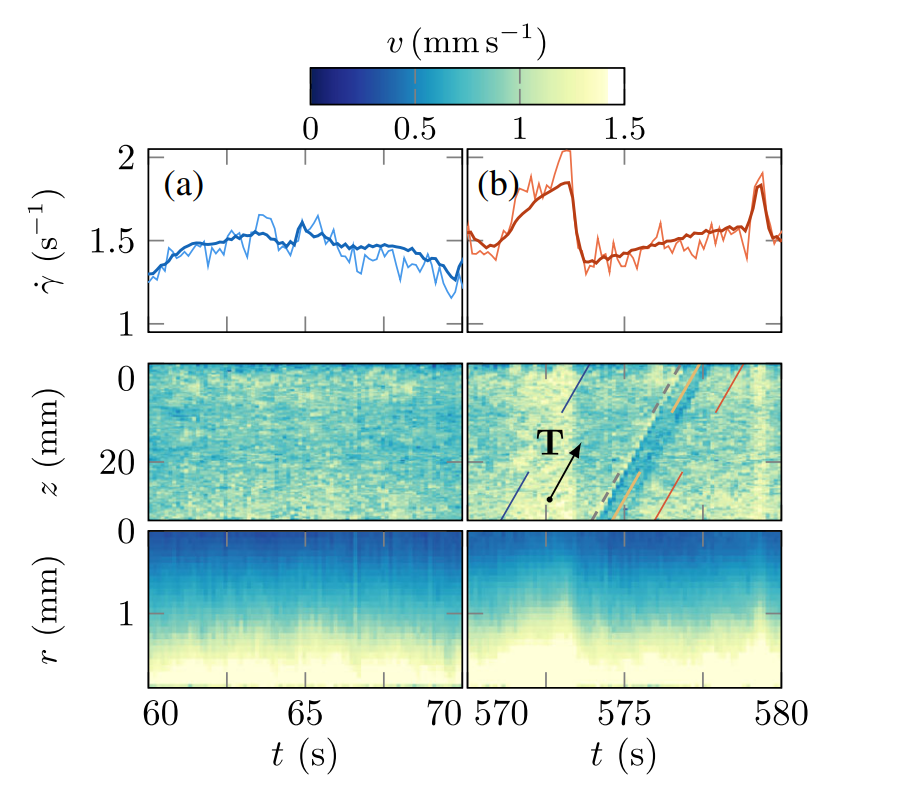

Cross-section of our rheo-ultrasound setup at Ens de Lyon. It allows us to measure the local velocity v(r,z) in the tangential direction (theta) inside the fluid annulus. From Saint-Michel et al., PRX 2018

These events propagate diagonally from bottom to top in space-time diagrams (see example below in Panel b), so they ‘pass by’ from the bottom to the top of our geometry with time. These bits of fluid in the band seem to flow slower than the rest of the fluid, which is quite strange. Their discrete, localised structure reminds us of what happens at the free surface of such fluids (as noted by the group of E. Brown and that of W. Poon) or at their bottom surface (through the nice setup of the group of D. Blair and J. Urbach), which could all be avatars of the consequences of force chains trying to (and sometimes succeeding) at messing up the measurement geometries (as suggested in a paper of the groups of G. Ovarlez and A. Colin).

Results of the experiments. Most of the time (left panels), the velocity map v(r,z) is featureless and simply follows that of the inner rotating spindle. However for some specific events (right panels), discrete propagative events are recorded.

Such phenomena guide numerical simulations by pointing how the suspension organises at the intermediate scales, larger than one particle but smaller than the whole of the fluid. Good simulations of shear-thickening fluids must then reproduce such features while remaining as simple as possible. The precise conditions under which these phenomena occur also help engineers design flow geometries or fluids to control (read: avoid or trigger on demand) shear-thickening.

General references on the topic

- M. Wyart & M. E. Cates, Phys. Rev. Lett. (2014)

- R. Seto et al., Phys. Rev. Lett. (2013)

- C. Clavaud et al., PNAS (2017)

- A. Goyal et al., arXiv:2210.00337 (2022)